Apollo Belvedere

Restoration as balance between technology and philology

New Wing – in person and live streaming

After almost five years, the Belvedere Apollo, one of the most illustrious and admired statues of the pontifical collections, will once again be visible to the public. The Directorate of the Vatican Museums and Cultural Heritage is proud to present today the study and restoration project, coordinated by the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities and carried out by the Stone Materials Restoration Laboratory with the Cabinet of Scientific Research. The complex and delicate intervention – made possible thanks to the generous support of the Patrons of the Art in the Vatican Museums – rose to the challenge of restoring a firm balance to the Apollo without compromising its marvellous harmony.

The statue, discovered in Rome in 1489 on the Viminal Hill, entered the Vatican between 1508 and 1509 at the behest of the pontiff Julius II, who was in the process of setting up the Courtyard of States in Belvedere with a composite iconographic programme focused on the mythical origins of ancient Rome. At the time, the Apollo must have been intact, missing only his left hand and the fingers of his right hand, but already in 1511 there are reports of the insertion of an “iron” element into the statue, perhaps for anchoring it to the wall of one of the niches in the Courtyard. Restoration work was carried out between 1532 and 1533 by Giovannangelo Montorsoli, who, Vasari writes, “remade the left arm that Apollo was missing”. In reality, contemporary engravings show that the intervention also involved the replacement of the right forearm and the integration of the top of the tree trunk on which the new arm thus rested.

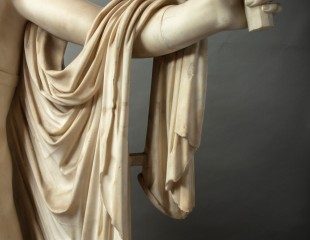

The numerous fractures that can be seen on the statue today – the plinth, the tree trunk, the ankle, the knee, the right arm and parts of the cloak – are the result of the sculpture’s long life, exposed outdoors since its discovery and subject to handling and movement, even of a certain magnitude, such as the Napoleonic transfer to Paris (1798-1815) and the more recent one, unfortunately not without problems, for the exhibitions organized in the United States of America (1983).

After examining various solutions, the current fragility of the statue imposed the decision to re-propose a support, as Antonio Canova had already decided, of a technologically advanced nature: the posterior element in carbon fibre, anchored to the plinth, uses only existing holes and recesses and is able to reduce the weight weighing on the most delicate fractures by about 150 kg. The pull provided by the bar also mitigates the imbalance of the centre of gravity towards the left arm which, leaning forward, is also heavily weighted by the cloak.

The posture of a slender Apollo with a bow and arrow, scenographic and possible to implement in the original bronze – dating back to 330 BC, possibly the work of the Athenian artist Leochares – is instead a rather risky solution in marble. Perhaps for this reason no other faithful replicas of this masterpiece of Greek bronze sculpture survived, although a copying tradition must have existed in the Roman age.

An extraordinary discovery in the 1950s enabled the recovery among the ruins of the imperial palace of Baia, north of Naples, of hundreds of plaster fragments belonging to a workshop that possessed casts taken directly from the original masterpieces of Greek sculpture of the fifth and fourth centuries BC, from which it was able to make faithful copies in marble for the rich patrons of the Phlegraean area. Among these plaster fragments, the missing left hand of the Belvedere Apollo was also recognised. It seemed fitting to take the opportunity of the present restoration to give the arrow-firing god back his “original” hand by inserting a cast of the “Baia cast” instead of Montorsoli's: the gesture has become more natural, the hand proportionate and light.

Another dart has been thrown and the scientific community will be able to judge the success of a philological experiment, which is in any case entirely reversible.